The Challenge of Predicting Patients at Risk for Falling, Part I

Patient falls can result in significant personal, financial, and emotional costs to patients, families, and institutions. Even without the physical sequelae of falling, the psychological fear of falling can precipitate a pattern of increased deconditioning, leading to other morbidities, disabilities, and even death (Hendrich, Nyhuis, Kippenbrock, & Soja, 1995; Hogue, 1992). Yet, predicting patients at risk for falling remains an elusive clinical problem.

In 1994, the patient fall rate in the authors' 606-bed tertiary care hospital was reported as slightly higher than the national average of 2.5 falls per 1,000 patient days (Morse, Morse, & Tylko, 1989), with some individual units experiencing an average rate as high as 7.4 falls per 1,000 patient days. Two clinical units had completed quality improvement studies on falls prevention and two other units were considering "prevention of falls" as a quality monitor. The unit-based studies were not research based; risk assessment tools were developed based on experiential data and assessments were not completed consistently. Each unit developed its own criteria for assessment and prevention and the results were not communicated throughout the institution. The purpose of this project was to select and implement a research-based assessment tool to identify patients at risk for falling and to develop a standard of care for preventing falls in patients identified at risk.

Design of the project

Team formation. An interdisciplinary falls team consisting of staff nurses, the nurse researcher, the risk management coordinator, a clinical specialist in gerontology, a nursing systems information specialist, and a physical therapist was formed to examine the issue. The initial goals of the falls team were to: (a) identify an admission assessment tool that would identify and predict acute care patients at risk for falling; (b) institute nursing interventions for this population; (c) increase hospital-wide awareness of patients identified at risk; and (d) educate the patient and family regarding ways to prevent home-based falls. A list of reasons for patients falls in the institution was delineated from the experiences of committee members and from incident reports provided by the risk manager.

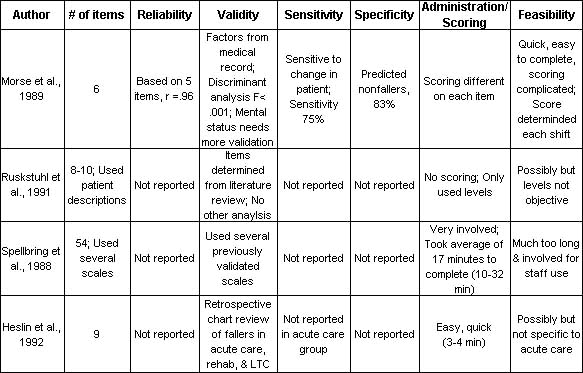

Review of the literature. With shortened hospital stays, an admission assessment scale was needed that would be valid, reliable, sensitive, specific, and easy to use. A literature search for a falls risk scale with acceptable psychometric properties (reliable, valid, sensitive, and specific) was completed. Articles for review were divided among members of the falls team and evaluated using the Criteria for Utilization of Research in Nursing (CURN) protocol (Horsley, Crane, Crabtree, & Woos, 1983). A grid was developed integrating the literature review into a comprehensive format that included a critique of the study and its applicability to our patient characteristics (see Table 1).

Assessing Fall Literature

From the more extensive review, four articles that addressed risk-assessment scales in acute care patient populations were initially selected for more intensive review (see Table 1) (Heslin et al., 1992; Morse et al., 1989; Ruckstuhl, Marchionda, Salmons, & Larrabee, 1991; Spellbring, Gannon, Kleckner, & Conway, 1988). Each tool was subsequently discarded for various reasons. The Morse Scale reported the most complete examination of psychometric properties. However, the items in the scale did not seem to reflect risk factors identified in the institution's current complex population of patients. For example, all hospital patients have more than one diagnosis, and almost all patients have an intravenous (I.V.) catheter or an I.V. lock (Morse et al., 1989). The study reported by Ruchstuhl and colleagues (1991) was not clear in its definitions of the variables that placed patients at various levels of risk for falling.

Spellbring and associates (1988) used a variety of assessment scales resulting in a very lengthy assessment, taking an average of 16.9 minutes, with a range of 10 to 32 minutes. While this assessment process could be used to identify other patient care needs in addition to the risk for falling, the team determined that today's busy nurse would not have time to complete this assessment with each change of patient condition. Heslin et al. (1992) provided the most feasible scale for use in our patient population; however, the scale had not been validated in an acute care population and scores were arbitrarily determined for each item. The purpose of the team changed from identifying a falls risk scale to developing a scale that would predict risk factors in our complex, acutely ill patients.

Scale development

Monitoring experience with the Braden Scale in this institution, which is used on all patients for predictability of skin breakdown (U. S. Department of Health & Human Services, 1992), found that the scale was completed on admission but was rarely used during the remainder of the patient stay. Therefore, the team determined that a fall-risk assessment scale that was predictive on admission would be the most feasible solution.

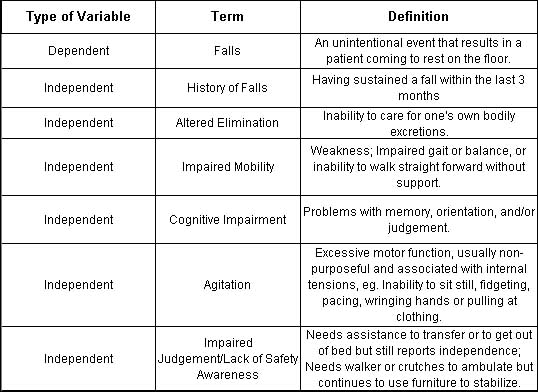

Benchmarking or comparing fall rates among hospitals and other nursing facilities is difficult and often inaccurate due to the lack of a consistent, standardized definition of a "fall" (Schroeder, 1995). Through general consensus and the literature review, a fall was defined as "an unintentional event that resulted in a patient coming to rest on the floor."

Key predictors identified in the literature review and in our population were listed. A grid that included the definition of each term used in previously reported studies and the statistical significance of each factor in relation to falling, if reported, was designed. The following factors were reviewed and considered: orientation/confusion, history of falls, medications, behavior/agitation, general weakness, immobility, sensory impairment, frequency of incontinence, I.V. lines (capped and open), diagnoses, alcohol abuse, ambulatory aids, postoperative status, language barrier, orthostatic symptoms, and age. Since studies frequently used different terminology and definitions, terms were combined into categories for ease and efficiency of analysis. These included immobility, impaired balance, impaired gait, decreased balance, use of ambulatory aids, and weakness. History of falls and age were indicators in all of the scales; however, age in itself was not statistically significant (Morse et al., 1989; Spellbring et al., 1988; Tack, Ulrich, & Kehr, 1987). Symptoms associated with increasing age (impaired mobility, diminished vision, and disease-related impairments) were more statistically predictive than was actual age (Morse et al., 1989; Spellbring et al., 1988; Tack et al., 1987).

Definitions for Fall-Risk Assessment

Based on the literature review of statistically significant indicators, the preliminary falls risk-assessment scale included ten indicators, divided into four categories. The categories were history of falls, altered elimination, immobility, and cognitive impairment. Definitions of each category were derived to provide clarification of each indicator (see Table 2). Three categories were based on patient report and one category on nursing assessment and observation. The scale was pilot tested for feasibility by three nurse members of the falls team. The scale took approximately 1 to 2 minutes to complete and patients could easily and quickly answer the questions. Based on feedback from the pilot work, final modifications were made.

Donna Conley, BSN, RN, is staff nurse, Maine Medical Center, Portland, ME. Alyce A. Schultz, PhD, RN, is nurse researcher, Wiscasset Family Medicine, Wiscasset, ME. Rhonda Selvin, MSN, RN, is family nurse practitioner, Maine Medical Center, Portland, ME.

Reprinted with permission from MEDSURG Nursing, December 1999, Vol. 8, No. 6, pp. 348-354. Copyright 1999 by Jannetti Publications, Inc., Pitman, NJ.